Dirty Shirt Rock ‘N’ Roll: The Liner Notes

Jon Spencer's Blues Explosion Box Set, Mar 07, 2026(This is the first of a series of seven booklets of liner notes written for the Jon Spencer Blues Explosion’s series of remastered, reissued, deluxe CDs, which included this collection as well as Year One, Extra Width, Orange, Controversial Negro (live), Now I Got Worry, and Acme. All of them have been arduously remastered by Mr. Spencer and sound completely fucking dynamite, have tons of extra tracks and rarities, crazy liner notes by Yours T, and I have never been prouder of any gig I have ever had, ever. If you don’t have them, what are you waiting for? Find them on amazon.com RIGHT HERE RIGHT NOW and make sure to follow the Blues Explosion on facebook. – m.e.

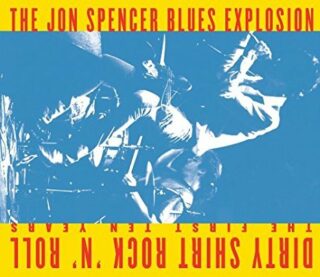

Dirty Shirt Rock’n’Roll — The First Ten Years

“The essential elements of our poetry shall be courage, audacity, and revolt.”

—The Futurist Manifesto of 1910

When Jon Spencer hollers “Blues Explosion!” it’s like a bazooka going off, a goddam elephant gun. Or a rocket launcher. It blows holes in things.

That you know it is coming does not diminish its impact. It shares the good-time gestalt and grind of James Brown barking Hit me!, Flavor Flav’s yowling, crackalicous Boyeeeeee!!!, Prez Prado taming his big band with a gutteral Uh!!!, championship wrestler Ric Flair celebrating his high style and bone-breaking brutality with a gleeful Whooooooo!! — or, for that matter, comedian Soupy Sales’ own trademark explosion, getting smooshed in the kisser with a cream pie. What the hell, everyone needs a signature riff.

“Blues Explosion!!!” — in which Spencer has reduced all of rock’n’roll to one semiautistic outburst — is well at home with this group. He shares every sweaty drop of their gusto, swagger, authority, conviction and control, as well as (especially in the case of Soupy Sales) their knowing absurdity and fearlessness. When the Jon Spencer Blues Explosion came shooting out of the womb in 1992, Clinton-era optimism was just beginning to ferment. But the landscape was still lousy with fifth-wave punks miming Black Flag and the Ramones; torpid Zep and Sabbath revivalism; and studied retro garage crud that quickly diluted itself into a fashion statement. Worse yet, a bumper crop of moping, belly-button-picking indie “rock” that didn’t rock (let alone roll) was about to be harvested and threshed into a new wave of pabulum for the college radio set — which should have been reason enough for even the spineless nerds in the glee club to drop out and turn on to a steady diet of Charley Patton, truck-driver crank and corn liquor.

The Blues Explosion live show was like a pie in the face to the entire scene — a real smackeroo that left ears and brains scorched, panties wet and grown men gone ga-ga. They were, without qualification, the best live act of their time and, across the paleontology of rock ’n’ roll, right up there with The King, The Godfather and The Stooge.

Spencer may have been the focal point, but the other two men in this jihad, Judah Bauer and Russell Simins, posed no small threat. Simins’ take-no-prisoners approach to the drums — thrashing, swinging and leaning into long locomotive rolls on the snare drum — and Bauer’s thump and twang, yanked from his Telecaster with oily precision and venom — were the thermonuclear core of the reactor. Except for lack of a traditional four-string bass — Spencer’s guitar, which often sounded somewhere between a vacuum cleaner and a well-tempered garbage disposal, was usually more than enough to hold down the dirtier end of the sound spectrum — the Blues Explosion was every bit a band in the classic sense. There were no extra parts. No one was replaceable. Spencer had already made his mark fronting Pussy Galore, one of the most willfully confrontational groups of all time. They had juggled with Molotov cocktails of punk rock, Stones-isms and noise. With Blues Explosion, he stripped it down to a jet-powered race car that took off so quickly it obviated the need for rearview mirrors. It was the futurist model of an old-style R&B review, performed with the subtlety (and self-referential bliss) of Jerry Lee Lewis having at it with a pneumatic drill. And when Spencer hollered “Blues Explosion!” the room shook.

Was it a celebration, a warning or a declaration of principals? Or was it some kind of elaborate joke?? Perhaps he was testifying to his own optimistic but very real belief that in rock’n’roll there was deliverance. Sometimes it sounded like they were kicking the bejeezus out of the previous 30 years of rock’n’roll simply because they could. But the truth of the matter was that this shit moved.

So what if Spencer boosted bits from Johnny Cash and Jet Screamer? Evolution was too slow, so he created his own musical language. Sure, some of it was pastiche — a patina of greaser sexabilly smeared over a bedrock of brutal guitar clang and buzz, punk rock, irreverence, ass-shaking rhythm, rebellion and, well, shtick. And why not? A guy howling “Blues Explosion!” — or variations on a theme, e.g. Blooooooooozzzzzzze Explooooooooossion!!, Blooooooooozzzzzzze Explooooooooossion!!!!! or the deceptively simple, recondite “blues explosion” — and gesticulating wildly across the elements of a vintage theremin, is prima facie ridiculous. But no more ridiculous than a screaming black queen from Georgia covered in pancake makeup and mascara, hair piled high, pounding out pumped-up boogie-woogie and pretending to like girls; or a French guy painting a moustache on the Mona Lisa and declaring it a masterpiece; or the generally held belief that an electric guitar distorted and amplified beyond any normal human pain threshold is somehow desirable.

* * *

The first Blues Explosion recordings were lo-fi and skuzzy, nasty, frantic, in-the-gutter rock’n’roll steeped in Sun Studio exorcisms, New York street punk and avant-garde pranksterism. The cover of their self-titled debut featured a bass drum adorned with the unequivocal legend “punk rock,” painted in a style perhaps best described as “mentally deficient DeKooning.” The follow up, Crypt Style, featured a portrait of the band sleazed to the teeth in hooker-red lipstick and eye shadow. They stood unapologetically as a challenge to every other group on the planet.

And then someone flipped a switch. It was like a blast of monster-making B-movie radiation — whereas the nascent Blues Explosion sessions sounded as if they were percolated in sludge and cast in pure raunch, the new record, Extra Width (1993), rose up like a shiny fucking beast.

Well, sort of. Spencer still seemed as interested in what kind of damage he could perpetrate with an SM-57 microphone loaded for bear and dripping with ungodly amounts of compression and slap-back echo as he was with elocution, but who cared? There would be plenty of time for that later. Extra Width came slamming out of the speakers with the slippery, penetrating funk of “Afro,” and whatever it was actually about, whatever he was saying, who could possibly give a fuck after you got hit with that riff, and that indelible groove, and did it even matter??

“Afro” was the greasy soul music version of the final moments of 2001: A Space Odyssey — here we were looking forward through the past to discover what we really were, and who we would become, and the answer was . . . Blues Explosion! “Afro” was a riot, the kind of slyly incomprehensible dance number the depths of whose perversity (like the Kingsmen’s “Louie, Louie”) were only limited by the imagination and sickness of the person listening to it. This was no accident. There was a real, adult dedication to concept and execution, a profound understanding of rock’n’roll history, unrepentant deconstruction and, goddam it all, the dirtiest and most misunderstood word in the critic’s notebook — postmodernism.

In the history of rock ’n’ roll, plenty of people made good records, but there are only a handful of innovators. No one works in a vacuum, and the avatars of the art form have always been the ones to choose their ingredients carefully before distilling their own brand of white lightning. The Blues Explosion was starting to blend low-brow sleaze and newfound studio sophistication with seamless alacrity. They were connecting the dots between Detroit, Memphis, Compton, New Orleans, Nashville, the Mississippi Delta and the Bronx, and the results were enough to make you drive your car, Lemmy Caution–style, off the road and straight into the future.

If “Afro” hit the ball out of the park, the lead-off number on Orange (1994), “Bellbottoms,” smacked the fucker so hard it never came down. First of all, who else would have the unmitigated gall and chutzpah to rent a string section to filigree their fuzz box? And here comes Spencer, pimp rolling like young Elvis, and he wants to talk about what . . . a pair of pants?? Bellbottoms! Or maybe it was about a girl. Bellbottoms! Whatever, it was another head-scratcher, that’s for sure. Nothing else had ever sounded quite like it, a riff-bashing, Dada speedball aimed squarely at the 30th century. But above all, it was catchy and it kicked ass. “Blues X Man” became the anchor of the live show, squeezing sparks out of a John Lee Hooker cock walk. Even on record its swagger is hard to beat. It is the only record where the singer actually wills you to turn up the volume, and it is the apotheosis of punk and blues twirling around the same liquored-up, one-chord axis. This is the covenant of Blues Explosion fulfilled, and it did for a new wave of postpunk blues primitivists what Helen of Troy’s face did for the armada. It was while touring Orange that the Blues Explosion began barnstorming the territories with the last of the great Mississippi bluesman, R.L. Burnside. This time the brickbats came from sissified muso-journos who were slack-jawed in fear of political correctness. Hadn’t this so-called Explosion already co-opted the Black Man’s Music for their own vulgar rock’n’roll? And now look what they were doing, dragging this poor old man around as a token in their minstrel show.

Truth was, of course, that Burnside would have sliced these white boys to bloody ribbons for seven nickels if he felt like it — he had already done time for killing a man. “”I didn’t mean to kill nobody,” he later protested. “I just meant to shoot the sonofabitch in the head. Him dying was between him and the Lord.”

More recently he was in the habit of drinking moonshine from a flask hidden in a child’s baby doll — you had to unscrew the head and suck the whisky straight out of its neck. Not a pretty picture. Most importantly, his slide guitar cut like a rusty straight razor, and his association with Spencer put him in front of real live drinking-and-fucking rock’n’roll audience eager to have their asses kicked by his low-down Hill-Country boogie and his X-rated repartee. It was the end-of-set jams with Spencer and the boys that grew into their collaboration A Ass Pocket Of Whiskey (1986), the best pure, impolite, house-wrecking blues record since Hound Dog Taylor’s sloppiest sides, at least. The true believers got it, of course, but the moldy oldies and industry squares ran for cover. They never understood that the Blues Explosion was not coloring outside of the lines — they had redrawn the boundaries.

The follow-up to Orange, Now I Got Worry (1996) was an exploration of everything the boys had created. They were mining their own twisted world of post-Blues Explosion rock’n’roll and deep-fried soul, and were confident enough to return to some of their earlier, brain-injuring thrash and burn. But it is telling that Spencer chose “Chicken Dog” from Worry to open this collection — it holds much of the JSBX formula in its teeth. Break it down and it reveals a complexity that most bands could never cop. This was some advanced shit: competing, iconic Spencer/Bauer riffs, smart-ass studio trickery, roots-rock loyalty, salacious intent, coital stops and starts, and who else had the balls or wherewithal to truck down to Memphis and hook legendary R&B jester Rufus Thomas into reimagining his entire career into a groovy, three-minute blast of insanity? Thomas teased Spencer after the session, “It’s alright, I’ll sue you later.”

***

So many bands stay so blissfully retarded throughout their careers that it is amazing they don’t get to park in the handicapped spot at the supermarket. But the Blues Explosion refuse to make the same record twice. Acme (1998) (and Xtra Acme, four sides worth of outtakes, remixes and ephemeric spizzle, which some would argue is as powerful a statement as the totem that spawned it) was certainly the heaviest record they had made to date.

“Lap Dance,” the joint rolled with infamous filth peddler Andre Williams, was absolutely insidious in its grimy, difficult funk and unremorseful sleaze. The collaborations with hip-hop producer Dan The Automator and sonic alchemist Calvin Johnson, especially, were audio terrorism of a high water, but you can bet they rankled a few dyed-in-the-wool punks still working from the old playbook — the one that comes wholesale with the pinup girl tattoo, the leather studded belt and the Marshall half stack. At least one friend of mine, The Moderately Successful Punk Rocker (who had just put out his sixth enjoyable-but-ultimately-forgettable album of Ramones-inspired hot-rod songs) was seething. “Who the fuck does Jon Spencer think he is . . . and what the fuck do you call that?”

But like previous naysayers — the self-appointed pundits who tried to make themselves look tall by standing on the backs of others, and the blues purists doomed to dance with dinosaurs in the tar pits of antiquity — they could not stop the cult of the Blues Explosion, who kept coming up with new ways to clobber you right between the ears. They were selling out venues all over the world — the live show, despite the innovations they were perpetrating on their records, was still built on old-fashioned superdynamite soul power and, if anything, had only become more ferocious. Maybe it wasn’t “punk” anymore, in the same way Duke Ellington stopped playing “jazz” in 1943. But like Duke said, it didn’t matter what you called it, because after all, there are only two types of music — “good . . . and the other kind.”

It took a few years to gestate the next slab, Plastic Fang (2002), which is the last record of the first decade of the Jon Spencer Blues Explosion. For this they called in a few hands from The Rolling Stones’ own A-Team to twirl the knobs and direct traffic, and the result was a calculated masterpiece of pure rock ’n’ roll. Of course the same poltroons who once cried in their milk that Spencer’s vision was too far-out were now whining that he was spinning too much blues and not enough explosion. Meanwhile, imitators had been propagating like snakes in a swamp, stealing the recipe and repackaging it in primary colors for a more conservative audience. A few of the prettier ones had even made it all the way to the hit parade.

But nothing can refute the fact that this record was a fucking killer. Tune in and turn on to “Money Rock’N’Roll.” The production sparkles in a way that would have been unimaginable circa Crypt Style, but the chucka-hucka rhythm of Bauer’s Telecaster and the sick funk of Simins’ beat are greasier than ever, the neoplatonic ideal of what rock’n’roll should sound like at the beginning of the 21st century. The guitars are so sloppy and perfect they sound like drunken kung-fu, and Spencer’s trademark spew is as down in the mix, suggestive and incomprehensible as you could ever want. What’s he saying? Something about Joe Strummer, the New York Knicks and a line lifted from James Brown’s Live At The Apollo? It is the rock’n’roll equivalent of all the lights on the pinball machine going off at once. Which is, presumably, why you put the quarter in the slot in the first place.